Minting in Cieszyn in the Middle Ages

The autonomous Duchy of Cieszyn was established at the end of the 13th century by its first Prince, Mesco I (died c. 1315), the oldest son of Prince Vladislas I of Opole (died in 1281). The division of the quite extensive Duchy of Opole and Racibórz significantly influenced the monetary situation in Upper Silesia. In a short time more than a dozen small states were established (c. 1323 – ten of them), including the Duchy of Opava, which became increasingly strongly linked with Upper Silesia – and later also the Duchy of Krnov. The rulers of these duchies tried to consolidate their positions and in addition increase their income by putting their own coinage into circulation.

Mesco I took over all the privileges of his father, including those concerning the right to mint. There was a mint master at the Prince’s court from the very beginning. Monetarius noster Tessinensis by the name of Fritto was mentioned in the last decade of the 13th century. He owned some land outside the town, which was later bought by a knight called Bogusz who founded the village of Boguszowice. The presence of Fritto at the princely court does not prove whether coins were actually minted in Cieszyn at the end of the 13th century since the term monetarius could describe the person in charge of collecting duties for the Prince. Nonetheless most researchers assume that he was actually a mint master brought to Cieszyn by the Prince in order to set up a mint in the new capital. It is less probable that he was a so called local moneychanger who carried out recoinage on market days. Whether the mint was finally set up is a separate matter. Still, in order to mint coins access to bullion is needed (which the Cieszyn Prince did not have); or funds to buy bullion, old coinage or silver scrap for re-melting. No examples of coins dating from the times of Fritto and Prince Mesco I are known, although some may have existed but not survived, especially if they were bracteates. Bracteates, small silver coins, were struck in the whole of Central Europe, especially in the 13th century. They were made in a special minting technique with the use of a single die and a leather covered block. They were stamped on one side only which resulted in the same design being shown – in relief on one side and recessed on the other. This kind of coin struck on a very thin sheet of metal was easily damaged. In the area of Cieszyn Silesia only one bracteate has been found; in Grodziec in 1998 by Wiesław Kuś, an archaeologist from the Museum of Cieszyn Silesia. Unfortunately, the design is extremely unclear, but may depict a standing ruler surrounded by architectural motifs. Due to the fact that similar types of bracteates are unknown we may assume that the coin was struck in Upper Silesia.

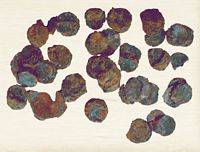

Only future discoveries will be able to answer the question of whether any coins at all were struck in Cieszyn as early as in the last decade of the 13th century. Nevertheless it is certain that the founder of the Cieszyn Duchy intended to do it and took steps to initiate his own coining production. It is worth mentioning that at the end of the 13th century most of the Silesian Princes gave up the systematic replacement of old coins by new coins i.e. recoinage. Instead their subjects had to pay a certain fee to the princely treasurer called seignorage. This also applied to Cieszyn townspeople, but the amount of the fee in the Middle Ages is not known. In the times of Mesco I the influence of his southern neighbour, Wenceslas II, the King of Bohemia, became progressively stronger. The Cieszyn Prince even established some family links with the Prague court by giving his daughter Viola in marriage to Wenceslas’ son, later to become King of Bohemia, Poland and Hungary as Wenceslas III. The growing influence of Bohemia was of great importance for monetary issues as in 1300 King Wenceslas II implemented a monetary reform in Bohemia putting into circulation in addition to denars a coin of greater weight and value, the heavy or thick denar (denarius grossus), therefore named ‘gross’ i.e. groschen (similar to the English groat), initially equal to 12 denars. Groschens were issued for the first time in the second half of the 12th century in Italy. So called deniers tournois (denarius grossus turnosus) were the base of the coinage reform in France in 1266. For Central Europe, however, the reform of Wenceslas II played the crucial role. It was carried out with the help of mint masters brought from Florence and the use of rich Bohemian silver deposits. Bohemian groschens were called Prague groschens (grossi Pragenses) although they were struck in the main mint in Kutná Hora. As they were produced of almost solid silver (fineness 0.930) very often they underwent the process of thesaurisation; that is accumulation and hoarding. It is proved for instance by the find of several groschens of King Wenceslas II which were discovered in 1800 in the garden of the Counts Larisch in Cieszyn (today – the Peace Park). In other locations, in Bażanowice, Polská Ostrava and Karvina not only groschens of Wenceslas II but also the subsequent Bohemian rulers, John of Luxemburg and Charles IV have been found. In 1999 a few dozen Prague groschens were discovered during the deepening of a pond in Czechowice. From the beginning of the 14th century Prague groschens became the basic currency in circulation in Silesia and were commonly used in Cieszyn Silesia as well, particularly since in 1327 the Duchy of Cieszyn had become a fiefdom of the Bohemian kings within the Lands of the Crown of St. Wenceslas. In the middle of the 14th century Casimir the Great, the King of Poland, had to agree on the incorporation of Silesia into the Bohemian Kingdom. Some other coins, smaller than groschens, also circulated in Cieszyn Silesia. In the second half of the 14th century small denars started being called hellers, from the Schwaben town of Hall where coins called denarius Hallenses or Halleri (later called Heller in German) were minted from around 1230. They had a fixed rate, therefore they were also adopted in Bohemia where initially they were worth one twelfth of a groschen, and in 1380 their rate was readjusted to one fourteenth of a groschen. On the other hand a denar was then worth one seventh of a groschen so 2 hellers were equal to 1 denar. During the reign of the weak King Wenceslas IV (1378-1419) Prague groschens also started losing their value dramatically. Hellers quickly became the common coinage in Upper Silesia as well. Some coins struck in other duchies of Upper Silesia were also in circulation in Cieszyn Silesia, which has been proved for instance by the discovery of a hoard of 80 coins minted mainly in Opava and Racibórz and dating from the second half of the 15th century. The hoard was found in 1994 in the Old Keep of Cieszyn Castle at a depth of over 12 metres. Almost a metre above the level of the hoard archaeologists found four French metal tokens dating from the 15th century. The tokens, metal discs with a pseudo-legend, together with an abacus were used by merchants and cashiers for reckoning in the Middle Ages and later. Sometimes they were also used as a substitute for coins. What function they carried out in the princely castle in Cieszyn is unknown.

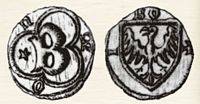

For a long time most numismatists were convinced that the first Cieszyn coins were struck after 1438, and the first Cieszyn rulers did not mint any coins at all or if so only sporadically. Recent discoveries and new interpretations concerning older coinage finds originally misclassified have changed these views. Nowadays the oldest known Cieszyn coin seems to be the heller of Prince Premislaus I Noszak (1358-1410) identified recently as part of a hoard from Nowy Kamień near Sandomierz (today in the collection of the District Museum in Bydgoszcz). The hoard was buried there some time about 1384 and included Prague groschens, denars of Casimir the Great and a small denar with a diameter of 12 mm and weight of 0.269 g. On the obverse is the crownless heraldic eagle facing right with a sash on its wings. The legend within the border reads MONETA DVD, the second D being a stylised and accidentally inverted letter C. Therefore the legend should read MONETA DVCIS. The legend within the reverse border reads THESCHI..ES with a letter P, the monogram of the Prince, in the centre. The chronology of the Nowy Kamień hoard suggests that the heller must have been issued before 1384, so it can only refer to Prince Premislaus I, and the first part of his rule. That should come as no surprise since he was by far the most powerful of all the Cieszyn Piasts, the advisor and right-hand man of Emperor Charles IV and King Wenceslas IV. He undoubtedly had both the motives and potential to consolidate his position in Upper Silesia by issuing his own coins. Passing over the hypothetical heller of Prince Vladislas II of Opole, the heller of Prince Premislaus I becomes the oldest known heller of Upper Silesian origin. It also initiated a group of Upper Silesian hellers, for example those of Opava and Oświęcim, a group characterised by the distinctive feature of the Prince’s monogram appearing as a device on one side which was most probably the result of Hungarian or Cracow influence. Other coins identified as originating in Cieszyn are hellers struck during the rule of the son and successor of Premislaus I – Prince Boleslaus I (1410-1431). One of them was found in the village of Nasale near Byczyna in the Province of Opole in a hoard buried around 1426 but lost again later. Its discoverer, a well-known Silesian numismatist, Ferdinand Friedensburg, identified it as a variant of a Bytom heller since there was a letter B on the obverse with O / N within the border; on the reverse there was the crownless eagle facing right and N / X within the border. Nowadays this coin is considered to have been issued by the Cieszyn Prince Boleslaus I at the beginning of his rule. The second heller, an original one also dating from that time, from the Wilczkowice hoard, is kept in the National Museum in Warsaw. Before the Second World War examples could also be found in museum collections in Bytom and Wrocław. On the obverse there is an uncial letter B with a tiny pentagonal star next to it with a trefoil surrounding them both. The first trefoils appeared on pfennigs minted in Vienna, and they were often copied in Bohemia, but rather rarely in Silesia. The legend reads MON. On the reverse there is a crownless eagle facing right on a Gothic shield with the letters B O above it and T I in the fields. The coin, which weighed between 0.24 and 0.29 g with a diameter of 12.5 mm, was very well struck but its short legend meant that in this case, too, numismatists usually link it with Bytom. Borys Paszkiewicz has claimed that B is not the first letter of Bytom but of the name Boleslaus, likewise BO on the reverse, while T and I refer to the word Teschinensis. It is assumed that the coin dates from the end of the rule of Prince Boleslaus I; that is around 1430.

Further fragmentation of Upper Silesia in the first half of the 14th century had an increasingly negative effect on the local monetary situation. For instance in 1417 John II, Prince of Racibórz, complained that 12 kinds of different coinage were in circulation in his Duchy. In order to generate a quick profit princes themselves issued excessive amounts of currency of lower denominations which they then exchanged for new coins, debased the coinage and manipulated the rate of exchange. Their subjects bore the costs of it all, especially townspeople, since the peasantry rarely possessed any money. The intervention of the Polish state against Upper Silesian princes’ mint masters who, without doubt with the princes’ knowledge, struck poor quality coins modelled on Polish ones or even their counterfeits, was unsuccessful. In 1438 Poland organised a punitive expedition which imposed an obligation on the rulers of Opava, Racibórz, Głogów, Opole and Brzeg not to allow any coinage modelled on Polish coins to be issued and be put into circulation in their lands. In the relevant document there was no mention of the Duchy of Cieszyn, which was then ruled by Euphemie, widow of Prince Boleslaus I. However, in 1441 one of her liegmen captured Cracow with a counterfeit.